Dover photographer sheds new light on old America  Yes, Thom Hindle still takes pictures for a living. You may have seen him bounding about town -- cameras gripped in both hands like six-shooters, saving the day for future generations -- and wondered if his devotion to Dover's history has eclipsed his own photography business on Atkinson Street. You may point out that he is the outgoing president of Dover's historical society, the Northam Colonists; that he heads up the Woodman Institute; that he teaches classes at the University of New Hampshire; and that he has published a coveted collection of stark images from Dover's past.

You wouldn't think there is much time left in the day for Thom Hindle. But his days don't end there. Apart from his efforts to resuscitate Dover's history while simultaneously keeping a handle on his business, he has further committed his time to immortalizing the purveyors of photography.

Yes, Thom Hindle still takes pictures for a living. You may have seen him bounding about town -- cameras gripped in both hands like six-shooters, saving the day for future generations -- and wondered if his devotion to Dover's history has eclipsed his own photography business on Atkinson Street. You may point out that he is the outgoing president of Dover's historical society, the Northam Colonists; that he heads up the Woodman Institute; that he teaches classes at the University of New Hampshire; and that he has published a coveted collection of stark images from Dover's past.

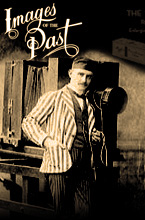

You wouldn't think there is much time left in the day for Thom Hindle. But his days don't end there. Apart from his efforts to resuscitate Dover's history while simultaneously keeping a handle on his business, he has further committed his time to immortalizing the purveyors of photography.Over the years, Hindle has amassed a staggering collection of photography's abandoned artifacts: over 100,000 glass plate negatives that summarize the huge body of work of 35 photographers. Many of those images have been resurrected into framed, hand-colored or sepia toned prints available for sale at his Dover gallery, "Images of the Past Gallery," and range from the highlights of Dover's heyday to the missionaries and miners of he Old West. But for Hindle, the images on display in his gallery are more than good art; they are life after death. History by leaps and bounds Hindle's fascination with the glass plate negatives, common to photographers from the mid-1800s to around the turn of the century, began in the 1960s when he was allowed to cart away a stash of them from a Dover attic. "I didn't know what I was going to do with them, but I didn't want to see them destroyed," he said.

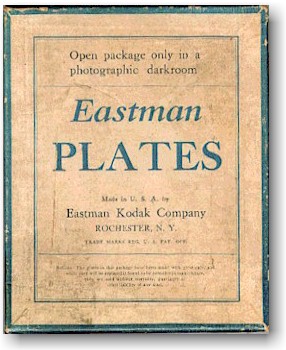

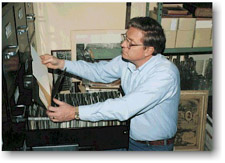

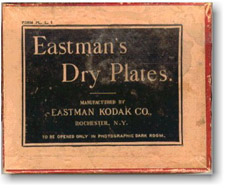

The glass plate negatives are especially difficult to maintain, not only by virtue of their brittle nature, but also as a result of the process used to form the negative. The plates were coated with a chemical or emulsifier -- collodion -- placed in the camera and exposed with an image. The first plates were inserted into the camera immediately after being applied with collodion. This precision process confined the art to the court of professional photographers. Later, dry plates allowed for wider use, but both forms are incredibly sensitive to the elements and require extra care to preserve. Hindle says the greatest threat to the plates is the risk of the emulsion being rubbed off during improper storage, usually from humidity. Hindle keeps his plates meticulously stored and cataloged in metal filing cabinets, each in its own protective acid-free sleeve and further protected by climate controls that even out temperature and humidity. Hindle makes a proof of each plate for reference. Space, however, is a concern, Hindle says. His "vault" is 10 feet by 12 feet, and already burgeoning with a collection that has more than doubled over the past few years. The enormous expense of preserving the plates is what ultimately compelled Hindle to convert many of them into prints for sale in his gallery, he said. Creating the prints was not without expense, though. To accommodate the process of turning negatives into prints, Hindle acquired a half-century old Elwood enlarger used for printing glass plates and then redesigned his darkroom. Not to mention the innumerable hours his wife, Mira, spends hand-coloring many of those prints before they're matted, framed, and offered for sale. The prints are reproduced by hand on fiber-based papers, and with proper fixing, washing and toning, Hindle says his prints will survive between 75 and 80 years.

The benefit, however, in addition to the unique prints that line the walls of his gallery, is that Hindle is now one of the few photographers around able to print glass plate negatives. Outgrowing DoverHindle's collection began as a means to preserve Dover images and its once-lauded photographers from the turn of the century. Indeed, Hindle's Dover collection alone is seemingly infinite. Most of the images have yet to see publication, despite a book of photos and numerous other reproductions in newspapers and along the walls of local businesses. Hindle's preservation of nearly a half dozen Dover photographers has produced some of Dover's most staggering visual recollections. Hindle has arranged slide-shows to outline the changes that have swept the city over the past century, and still works to chronicle change to the present day. Those initial images, however, have been joined by those of surrounding communities and even other states. "The collection now extends into other areas -- Rochester, Farmington, Concord, and Massachusetts," he said. "It also spans beyond New England." Among the prints for sale are images from the White Mountains, the coast of Maine, lakes of Vermont, and upstate New York, spanning autos to people to landscapes to the leisure activities of the past. "Dover is now a small segment," Hindle says of his collection. The element of surprise despite the financial and temporal burden of preserving the past, Hindle says that he is often elated when sorting through new acquisitions- . "That's the fun thing about this," he said. "You don't know what's in a new collection." Uncovering an historical treasure can be time consuming, though. Hindle says he spends anywhere from a few months to more than a year sorting through a new collection, a process that often ties up other work. "It occupies so much time," he said. Hindle says his commitment is occasionally overwhelming, but that without his attention, too many glass plate negatives -- snapshots of history -- would be lost. "A lot of studios would find boxes of glass plate negatives and just destroy them," Hindle said, adding that the cost of preserving them scared away most photographers, who saw no value in hanging on to them. "So many were dumped and destroyed." Hindle says he will continue his self-imposed mission of rescuing the past from carelessness, and also continue to offer people a means to reproduce glass plate negatives as well as archival copies of family photos. To compete, however, Hindle has finally been forced to bridge the business of the past with the commerce of the future: the Internet. Hindle recently introduced his own website, (http://www.imagesofthepastgallery.com), featuring some of the prints available for sale in his gallery.

The Images of the Past Gallery is located at 35 Atkinson Street in Dover. They can be reached at 603-742-7783. Preserving history is Thom Hindle's mission. A Feature Article In The Dover Times -

12/31/98

|

Worse for Hindle, the photographers whose careers had spanned the life of glass plates were being wiped clean from history along with their work. That prompted him to track down the families of local photographers and volunteer to grant them a new lease on life. "I started purchasing the glass plates with the idea of wanting to preserve the photographer's identity," he said. Not only did Hindle accumulate the negatives, but also many photographers' cameras and notebooks, rounding out a comprehensive picture of each individual. But as Hindle's collection grew, he realized that his commitment to the past was going to cost him considerable time and money in preservation alone.

Worse for Hindle, the photographers whose careers had spanned the life of glass plates were being wiped clean from history along with their work. That prompted him to track down the families of local photographers and volunteer to grant them a new lease on life. "I started purchasing the glass plates with the idea of wanting to preserve the photographer's identity," he said. Not only did Hindle accumulate the negatives, but also many photographers' cameras and notebooks, rounding out a comprehensive picture of each individual. But as Hindle's collection grew, he realized that his commitment to the past was going to cost him considerable time and money in preservation alone.